A pioneering painter who also taught at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Damascus between 1966 and 1987, Moustafa Fathi (1942-2009) was widely respected for his research of Levantine folk art in addition to his analysis of Syrian visual culture as a complete record of social advancement that stretched back to ancient times. One of the central ideas that Fathi identified in his reading of history was a profound connection to nature, particularly the diverse landscapes that shaped Syrian society as communities adapted to surrounding environments amidst political shifts—a relationship to the land that was articulated in various art forms. Although modern painters detailed the historical, cultural, and environmental factors that continued to shape the Syrian experience, Fathi was the first artist to reconfigure the aesthetic motifs that emerged over centuries of social development by returning to a basic structure from which new forms could be derived.

Recognizing that human thought stems from abstract concepts, Fathi likened the process of invention in language, art, philosophy, and so forth to the growth processes or “mechanics” of nature. Fathi demonstrated this theory by treating each painting as a site where regenerated forms organically emerge. Using a printing method that registered intricate cells of lines and shapes, Fathi allowed the different characteristics of his self-contained patterns to interact, eventually creating a dense grid of colliding or overlapping units as he intuitively positioned them within rectangular compositions. Vertical paintings reminded the artist of a written page while horizontal works resemble the arrangements of objects such as artefacts, rocks, and animal bones that were sprinkled across the floor of his studio as he mapped the layers of Syria’s terrain that accumulated over time.

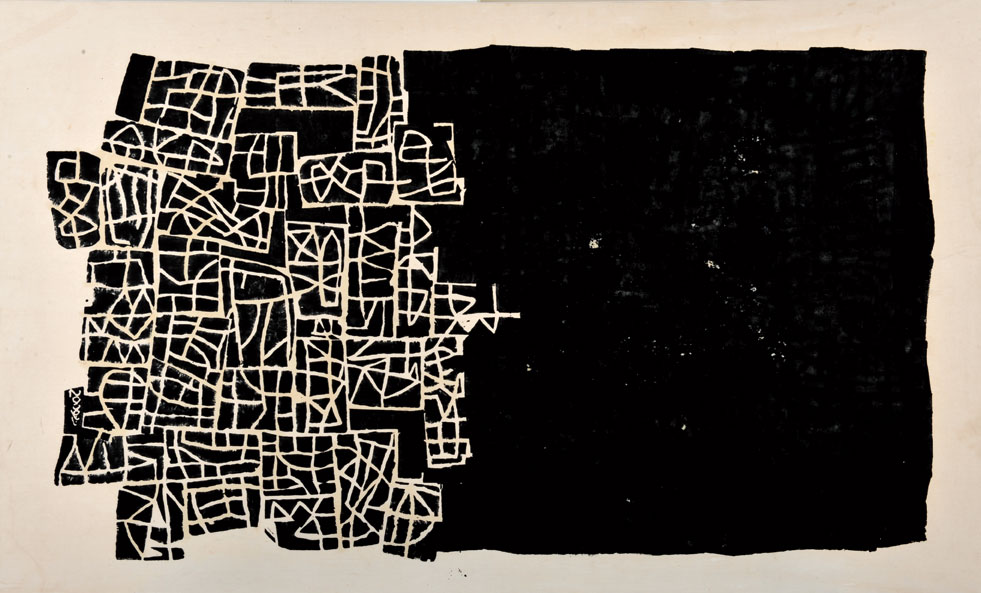

-Moustafa-Fathi-stamp.jpg) [An example of Moustafa Fathi`s woodblock stamps, based on an ancient design. Collection of Ammar Othman.]

[An example of Moustafa Fathi`s woodblock stamps, based on an ancient design. Collection of Ammar Othman.]

[Two examples of Moustafa Fathi`s woodblock stamps with his original designs.]

[Two examples of Moustafa Fathi`s woodblock stamps with his original designs.]

Often invoking the surface of the earth upon which natural phenomena occur, Fathi’s compositions appear to move across the subtle variations of saturated color fields that were rendered using natural pigments and applied to the canvas with water. Through this aspect of his work, he sought to “harmonize” with the “simplicity and perfection” of nature rather than imitate it. Fathi associated every aspect of his painting style to the “mechanics” of nature; his carved woodblock stamps, for example, were regarded as “dispersed stones on the land.” At the same time, his artistic “tools” represented "images shaped by human thought, man’s traces, and sometimes man himself." According to the artist, the patterns he adapted from diverse sources such as Palmyrene funerary art and Bedouin textiles and architecture were “living concepts.”

[Moustafa Fathi in his Daraa studio. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

[Moustafa Fathi in his Daraa studio. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

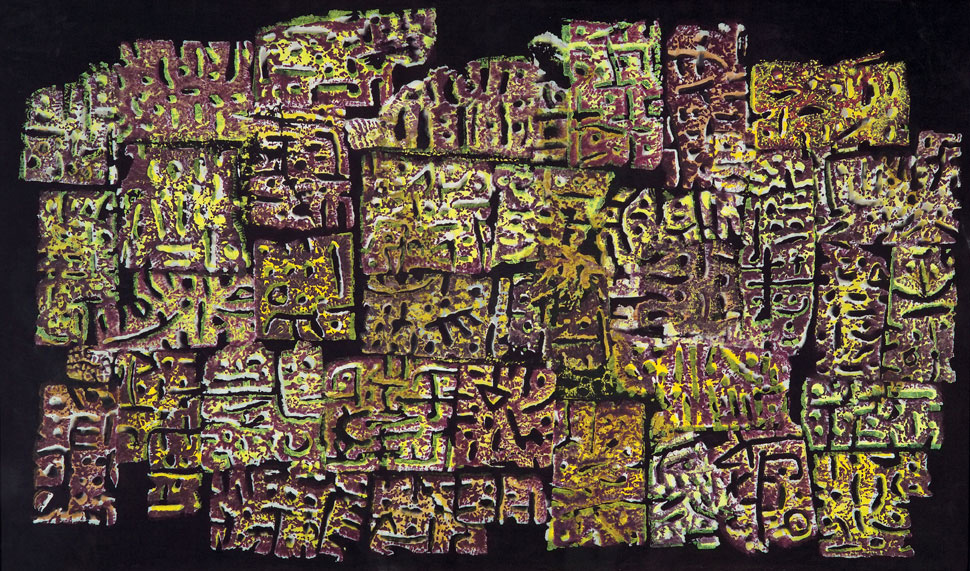

The works below span several decades of his oeuvre beginning in the 1980s, detailing the most prolific phase of his career. From 1987 to 1988, Fathi conducted intensive fieldwork in Syria, traveling throughout the country in order to document the aesthetic variations that fashioned its cultural memory. The featured mixed media on canvas paintings demonstrate the formal results of his groundbreaking study as he described nature, society, culture, and history as interconnected facets of everyday life.

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (1994). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (1994). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (2000). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (2000). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

Influences

Fathi’s earliest artistic experiences occurred while he was a child in Daraa, Syria. He first learned how to carve—a skill that became integral to his artistic practice—and later took up drawing at the age of sixteen when pioneering Syrian artist Mahmoud Hammad settled in his hometown. Although Hammad only lived and worked in Daraa as an art instructor for two years, he had a lasting impact on Fathi. Hammad had just returned from Italy, where he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, and was committed to chronicling Syria’s distinctive environments, such as the rural scenes of the Hauran region. In regard to his initial contact with Hammad, Fathi once told arts writer Rashed Issa: “His character fascinated me; and soon I decided to be a painter like him.”

Fathi studied with Hammad at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Damascus in the mid 1960s, where the latter was the chair of the Sculpture Department after serving as a founding faculty member. Hammad encouraged Fathi to experiment and to seize his own creative path, and also taught him the art of engraving. As a student at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Fathi witnessed one of the most dynamic phases of twentieth-century Syrian art. In 1964, Hammad invented Letterism, a new form of abstraction that reimagined the use of calligraphy in modern Arab art. The floating shapes that are essential to Fathi’s organic compositions recall the defiance of gravity that is seen in Hammad’s abstract paintings—the calligraphic forms that dissolve into colorful arches and lines, appearing to transform in real time. Decades later, when asked to name the Syrian artists who influenced him, Fathi identified “the great Elias Zayat;” expressed admiration for the “spontaneity of Fateh Moudarres;” and referred to the paintings of Mahmoud Hammad as “intellectual icons.” Above all, he proclaimed, “I cannot disregard anyone…every artist has something to say and we should carefully listen.”

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (2007). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (2007). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

In Syria, Fathi was given a solid artistic foundation upon which he could build. When he traveled to Paris, France to study engraving and lithography at the National School of Fine Arts in the 1970s, he not only absorbed the staggering range of art and art history that was presented in the city’s institutions but also searched for further evidence of Syria’s rich artistic heritage through its archeological collections. At the same time, contemporary art remained a central interest for Fathi, and in France he developed a deeper understanding of abstraction, particularly American and European movements. In the works of painters such as Henri Matisse, Paul Klee, and Jackson Pollock he saw connections to Islamic art, and continued to find links among diverse visual cultures throughout his life as an artist.

.jpg) [A section of Moustafa Fathi`s personal archive and library in Daraa. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

[A section of Moustafa Fathi`s personal archive and library in Daraa. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

[Moustafa Fathi`s works as they appeared in his Daraa Studio. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

[Moustafa Fathi`s works as they appeared in his Daraa Studio. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

Artist as Anthropologist

As an innovative painter and printmaker, Fathi embraced textile art, and avidly researched traditional art forms as they appeared throughout human history. His warehouse studio in Daraa was filled with a significant collection of artifacts, which he acquired as he studied Syria’s material culture. The artist’s interest in historical objects as anthropological evidence was spurred by childhood experiences. Fathi’s relatives lived in the ancient district of Daraa in a traditional house where interior and exterior environments were nearly indistinguishable: farm animals were kept near living quarters that were decorated with “ostrich feathers, cushions, wool carpets, and farmer’s clothes.” As a young man, Fathi often returned to sketch the traditional houses of the old city, viewing architecture as indicative of man’s relationship to the earth. These scenes became etched in his mind. Throughout his time in France, Fathi recalled the imagery of what he described as “the art of the farmer,” and eventually used the concept of assembling diverse objects as one of the aesthetic bases of his art.

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (1992). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (1992). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Outside Moustafa Fathi`s Daraa studio, a random selection of objects. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

[Outside Moustafa Fathi`s Daraa studio, a random selection of objects. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

[An earthwork by the artist, outside his Daraa studio. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

[An earthwork by the artist, outside his Daraa studio. Image copyright Nassouh Zaghlouleh, 2008.]

The Evolution of Form

In the early stage of his “printed” paintings, Fathi used engraved metal plates to execute works on paper. After exhausting the aesthetic results of this technique, he began to divide each plate into multiple sections in order to achieve “a new form in every print.” Despite employing the concept of repetition by limiting the number of his incised tools, he rearranged his motifs and rarely duplicated a composition. The challenge of creating individual works with a technique that is traditionally reserved for printing editions led Fathi to explore other hybrid methods. Woodblock stamps allowed the artist to work intuitively, moving across the picture plane with little effort—a gestural yet controlled approach to painting. In addition to finding inspiration for the designs of his stamps in various examples of folk art, Fathi learned to use new techniques and materials when visiting Syrian cities and towns. During a research trip to Aleppo, for example, he met with fabric designers, and soon began to work on canvas and with synthetic inks. Fathi articulated his receptiveness to diverse art forms by stating: “If you could see your country as a huge atelier, then life would be so rich.”

.jpg) [Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (2000). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

[Moustafa Fathi, Untitled (2000). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery.]

Ammar al-Beik`s 2008 video essay Moustafa

*Author`s note: All quotes are excerpted from a 2008 interview with Moustafa Fathi conducted by Rashed Issa, recently translated from the Arabic by Fedaa Alqaq.